“Admiration is happy self-abandon; envy, unhappy self-assertion.” - Soren Kierkegaard

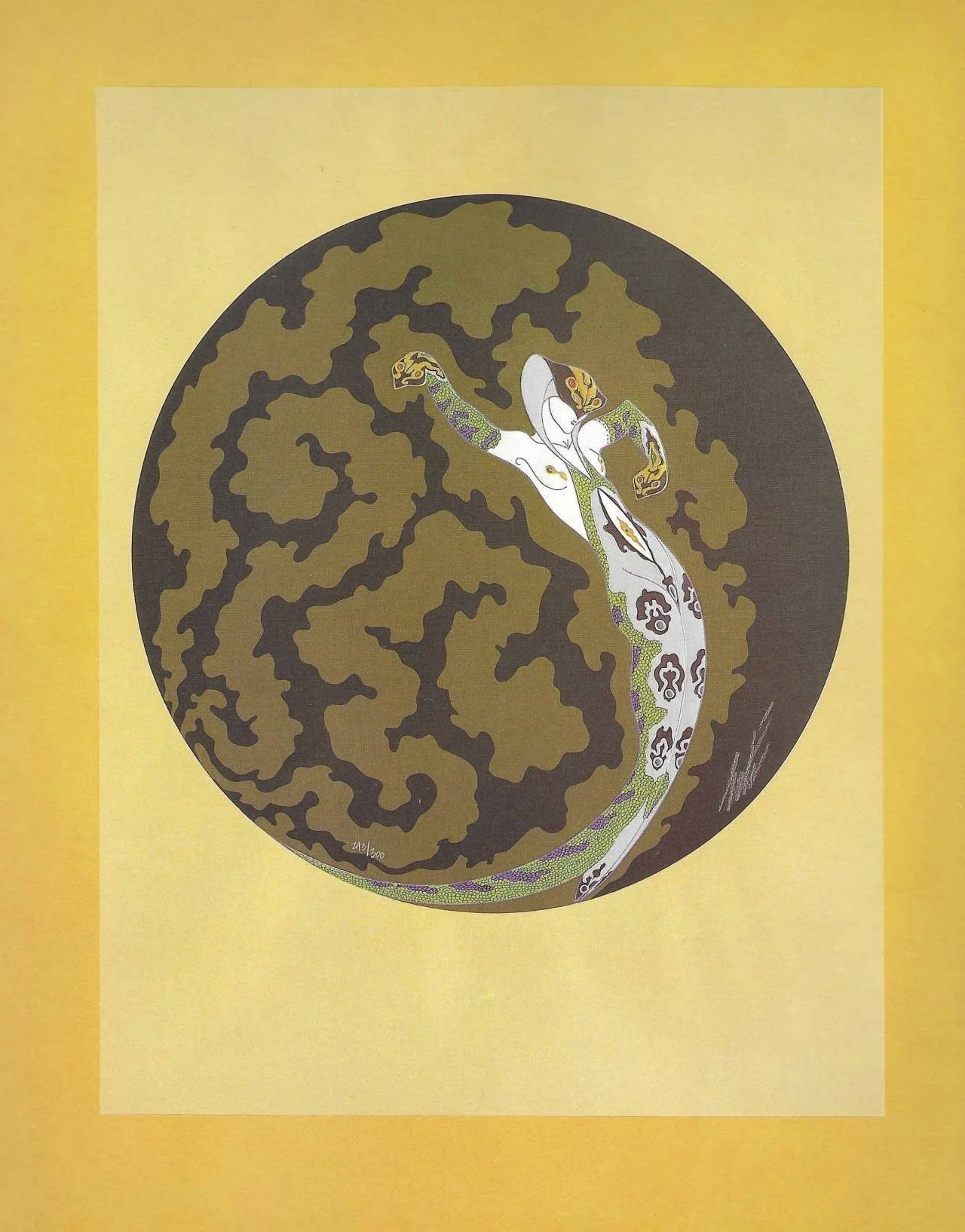

'la jalousie' by erté

—

When I checked out a memoir-adjacent book about sex work and the art world from the library 6 months ago, I was excited to read a whole volume focused on the overlap between these two fields that constantly cross-pollinate, both throughout history and in my own life.

But the first thing I did was research the author.

The closer a woman is to my age, the more inherently competitive I feel with her. If I believe her to be more attractive, financially thriving and/or interpersonally successful, I cannot control the swarm of insecurities that sizzle through me as I compare myself to her.

Despite enjoying the intelligent yet unostentatious writing style and the smoothly-incorporated intertextual references, once anecdotes detailing the writer’s personal experiences in navigating [high-end] sex work and the [similarly high-end] New York art scene began flowing, my long-indulged inclination toward female comparison kicked in. And when specific dollar amounts–mainly sex work rates or, in one instance, the exorbitant cost to enter a gallery for some tangentially-related exhibit–were mentioned, I became physically and psychically uncomfortable as my whole being responded to this information with distaste and disdain.

What underlies the above malaise is the begrudging acknowledgement that if I had only dedicated more time and effort to the pursuits; restrained my fervent revulsion toward the pretentious and the pompous; retrained the reactionary facial expressions and bodily reflexes that never fail to betray my words, then that could have been me, that could have been mine. The fact that I did not attests to many traits that are liabilities in both sex work and the art world: an inability to convincingly maintain a seductive, engaging persona; a struggle with addiction to substances (fused with sex work by the beast of immediate gratification: an escape from one bump, a bundle of money for one hour); a desire for regular, reliable income that does not involve the same need for constant self-protective vigilance; a lack of discipline to direct toward taming into submission the always-growing number of things I don’t genuinely enjoy…

I have abandoned the book, halfway through.

–

This phenomenon teleports me back to very early sobriety–and sanity–almost a decade ago. I had such a minimal sense of self that everyone and everything entering the horizons of my awareness felt like a mortal threat to my nascent, barely-sentient personhood. It was so bad that I felt palpably agonized when I listened to certain musicians or looked at the works of certain artists—especially female ones, especially those near to my own demographics—because they filled me with dread and helplessness. I automatically transformed every creative product into a fossil of who and what I could have been but was, in fact, not, nor ever would be. (Mind you, I was, like, 24.)

Once I was able to detect that envy was at the root of this overwhelming, confining mentality, I fiendishly sought out books and articles on the subject, as though to amass knowledge about a character defect constructs the impetus to dismantle it, too. I remember feeling frustrated by the paucity of resources, a sentiment expressed in the introduction to Envy: A Theory of Social Behaviour by Helmut Schoeck. The Austrian-German sociologist’s exhaustive examination of envy’s role within society and culture opens with a foreword decrying the dearth of previous writing and analysis on the subject.

Why is this the case? Although a long- and up-standing member of the seven deadly sins (as finalized by Pope Gregory I in the 6th century), the subject matter of envy has not been taken up as widely and rigorously as its siblings. However, when ruminations do occur, they are often placed in the context of the other fatal fellows. Chaucer notes that “every other kind of sin is in itself pleasurable, to some degree productive of satisfaction, but envy produces only anguish and sorrow.” Kant states that “envy is the very antithesis of virtue, the denial of humanity,” and that, due to its “purely destructive passion,” envy is “unproductive of any positive value for the individual or for a society,” rendering it “an infringement of duty.” St. Thomas Aquinas outlines three stages of envy: 1) attempts to lower the envied person’s reputation; 2) either “joy at another’s misfortune” or “grief at another’s prosperity” are felt, based on outcome; and 3) seething loathing, because “sorrow causes hatred.” Nietzsche pronounces that some men’s failures result in the wish that “the whole world perish,” which “is the pinnacle of envy, whose implication is ‘if I cannot have something, no one is to have anything, no one is to be anything.’” Schopenhauer, along with reflecting that “of all animals, man alone torments his own kind for entertainment,” also believes envy to be “the soul of the alliance of mediocrity, which everywhere foregathers instinctively and flourishes silently, being directed against individual excellence.”

A common element to these philosophical giants’ declarations is that envy simply does not make its bearer feel good. Though they are all “sins” for a reason, at least some level of enjoyment is possible with the euphoric sensation of lust; the comforting satiety of gluttony; the laser-focused accumulation of greed; the deeply-held assurance of pride; the luxurious leisure of sloth; and the cathartic extremity of wrath.

—

Is it possible, however, that we have been interpreting envy as consisting of bleak, counterproductive dimensions that might not always be accurate? What if envy were to be amputated into its individual components? This is a hypothetical practice that Sianne Ngai, in her book Ugly Feelings, feels “is impossible,” given the inability “to divorce the pervasive ignobility of this feeling from its class associations or from its feminization.”

Yet, if we were to try, it might be said that the initial harbinger of envy is its identification of a powerful craving, which is the basis for Elise Loehnen’s meditation on the topic in her recent bestseller, On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good. She begins the chapter describing that, because it “requires us to own our wanting, envy is the fulcrum, or hinge, for all the other Deadly Sins: to voice desire, to want something, is the first expression of agency.” Loehnen reiterates the aforementioned belief by noting that, while “envy is a gateway for the other sins,” it is also the only one that “offers zero sustained pleasure.” What we each actually do with our individual desires—once ascertained and acknowledged—involves a complex concoction of both intentional and inadvertent cognitive reactions. After distinguishing what is held to be most important, an array of options blooms, ranging from invigorating motivation to navel-gazing dejection, and beyond.

The recognition of a strong desire tends to be fused with an increased awareness of how access to and possession of the yearned-for is distributed—especially, as we have been told, by women. Ngai’s argument on envy and feminism delves into the perception of envy as a pointedly female-coded “negative affect.” Citing a trove of historical sources, she writes that “by the 20th century women were viewed as ‘more susceptible’ to envy and jealousy than men” and that “the same passions were increasingly viewed as, ‘on several counts, more inexcusable in a woman than a man.’” This, she warns, “should alert us to the fact that forms of negative affect are more likely to be stripped of their critical implications when the impassioned subject is female,” revealing a “larger cultural anxiety over antagonistic responses to inequality that are specifically made by women.” As Ngai proves, envy has been “moralized and uglified to such an extent that it becomes shameful to the subject who experiences it,” as well as “stripped of its potential critical agency–as an ability to recognize, and antagonistically respond to, potentially real and institutionalized forms of inequality.”

This speaks to another of envy’s fundamental aspects, in addition to the discernment of what a person values most. It could be contended that a significant sense of justice–though it may be quite a twisted one–undergirds the notion that what the envied has, the envier should, at the very least, have too (or, better yet, instead). And if not, then the former should not have it in the first place. As Ngai explains, envy “remains the only agonistic emotion defined as having a perceived inequality as its object.” But Schoeck notes that the individual dominated by envy is nevertheless aware “that in the long run, it would be a very demanding responsibility” were he to acquire the envied man’s qualities or assets. He convincingly declares that “the professional thief is less tormented, less motivated by envy, than is the arsonist.” Thus, “the best kind of world” would be one in which nobody has these advantages, bringing forth a reality devoid of the majority of pleasures–but at least equally so, for all.

–

Aside from this steadfast dedication to a warped, self-serving justice, theories surrounding why envy leads to destruction abound. Ngai includes in her written dissection Kierkegaard’s proclamation that “envy is concealed admiration,” and that if someone “senses that devotion cannot make him happy, [he] will choose to become envious of that which he admires.” It is notable that there is the suggestion of a conscious choice, a decision made before that which is appreciated and desired festers into the deplorable sin of envy. Once this happens, Kierkegaard alleges, “he will speak a different language,” and “will now declare that that which he really admires is a thing of no consequence, something illusory, perverse, and high-flown.” This differs from the previously detailed theories, because it implies that the envier knowingly denigrates what was originally held to be so precious, resulting in a negation of the initial perception of worth. One method that can be employed to vacate something’s value is to literally cause it to cease to exist; however, this does not necessarily alter or erase the assertion of the now-spectral object’s merit.

In the first of his sporadic mentions of envy studding the text of On Balance, prolific psychoanalyst-cum-author Adam Phillips points out that “there is always a magical belief that by destroying the thing we love, we destroy our need for it.” For her part, Loehnen transmutes demolition into transcendence, writing that one feasible strategy is to adopt the armor of enlightenment, to believe that we have overcome “the baseness of desire and are content to embrace whatever life gives us, as if the solution to all this wanting is to unhook from wanting anything at all.” Though this remedy may be all but out of the realm of human possibility, its core spirituality is more appealing to me than it would have been a few years ago.

As even many non-addicts know, Alcoholics Anonymous and its offshoots incorporate, first mentioned in the second of the 12 steps, a “power greater than ourselves,” also referred to as “God as we understand Him.” Without getting into a chronology of AA or a religious diatribe, the crux is that for 10 full years now, I have heard, read, and thought about this concept regularly, and am yet to come to any concrete conclusions of my own (when discussing something so amorphous, to even use the word “concrete” feels inappropriate). During my twice-to-thrice-yearly solo girl’s trips, in which I rent a car and careen off to parts personally unknown, I’ve had extraordinary moments in nature, moved to tears contemplating the universe, whether soaking in a hot tub while it’s snowing or sitting cross-legged on the brim of a lake filled with lily pads. Unfortunately, any serenity secured from these sojourns gradually—and then, once the city limits have been breached, rapidly—melts away as I inch closer back home to NYC and reality, reactivating cellular data for the MTA app and remembering how much of a mess my insanely expensive apartment is. I can’t say if a sustained, solid belief in a power greater than myself would actually assist in eliminating—or at least, perhaps, decreasing or reframing—my tendency toward envy, because I have never experienced it. But based on what others have shared, some features of such a faith are: feeling that one is in the right place at the right time, even if it doesn’t appear that way; believing that there is a larger plan superseding one’s individual actions; trusting that events in one’s life have reason and meaning.

It’s tempting to think that snagging spirituality would be the thing that finally frees me from my envy, especially because it has definitively not happened yet, so I cannot say, from experience, that it would fail like all else has. Then again, I haven’t achieved the creative virality or critical acclaim or financial windfall I desire either; but the latter bunch are still in line with the material, human-made parameters I’ve lived for and by, and the former is not.

–

I began to see that I was subconsciously harboring as a fundamental belief that there is a finite amount of success, happiness, and other associated Good Things available in the universe. Hence, anyone’s staking a claim to a portion of what was perceived to be a sparse quantity, by definition, decreased the likelihood of my doing the same. Schoeck mentions “the false premise that one man’s gain necessarily involves the others’ loss,” and Loehnen portrays the same concept as “that sticky myth of scarcity, the game of musical chairs.”

Although this view is indeed erroneous based on the criteria I now realize I meant, it’s not irrational, as its roots fit firmly in the framework of the lifelong woman-versus-woman, bitch-eat-bitch tournament in which we are entered without our consent. Even if the proportions of my comparison and resultant envy may be more outsized than the average, the notion of women existing within an innate competition is firmly entrenched in society, worldwide. This kicked off with the all-important marriage-securing and husband-landing, as an early twentieth-century Max Scheler quote included by Schoeck sums up: “The woman, because she is weaker and hence more vindictive, and by very reason of her personal, unalterable qualities is forced to compete with other members of her sex for man’s favor, generally finds herself in such a ‘situation’ [beset by envy].” Could anyone be truly surprised by the germination and cultivation of envy when women are unwittingly, unwillingly situated as opponents?

Reflecting on why envy has ended up so intertwined with the female gender, what comes to mind is that it tends to be delineated by a stewing inactivity, and this proclivity toward passivity has historically been correlated with women, as opposed to the intrinsically take-charge, action-oriented male figures. Also, it’s not a stretch to suppose that the extreme societal constraints placed on the appropriateness of women’s occupations, presentations and very identities throughout world history begat an interminable parade of frustrated phantoms, those would-be and what-if female existences. I’d imagine that witnessing the once-exceptional case of a woman defying cultural bondage and exercising a degree of agency typically relegated to the male sphere might inspire a reflexively envious response. That modern bogeyman The Patriarchy has undoubtedly, happily screwed women by deliberately limiting resources and thus creating an oft-desperate scramble for their acquisition. (Obviously, I am barely scratching the surface here, but you get the gist.)

Ngai’s expertly crafted chapter revolves around her critical analysis of the 1992 film Single White Female, an archetypal contemporary “story of female envy and emulation.” One of the major themes in the narrative is “that among women, even slight and supposedly easy-to-disguise differences” are likely to “lead almost immediately to hyperbolic conflict and violence.” Conversely, The Talented Mr. Ripley—which, thematically, could be considered the movie’s male equivalent—proposes that the disparities in socioeconomic positions must “be enormous to culminate in violence between men.” Ngai believes that the chasm “between the scale of the class differences” which inspired the opposing cinematic “aggressive mimetic behavior” both “exaggerates the pettiness of female envy in contrast to male envy” and “contributes to the stereotype of women as unusually prone to envious hatred.” In the latter film, heroine Allie is displayed as “the embodiment of a feminine ideal,” the admiration of whom “is to be expected, even mandated,” yet “any act of striving toward that ideal” by antagonist Hedy is branded “troubling or problematic.” So, basically, if we didn’t have the fairy-dusted good fortune to be born and bred as a societal paragon, we’re shit out of luck.

This juxtaposition between female and male versions recalls–and complicates–a thesis repeated multiple times by Schoeck: that envy is near-exclusively formed and fomented in relation to someone relatively close to the envier’s own social position. As such, the faraway king on the throne is unlikely to be the figure inspiring intense envy among his subjects; rather, it is the nearby neighbor who encapsulates the “that should have been me” mindset. Schoeck explains that “overwhelming and astounding inequality, especially when it has an element of the unattainable, arouses far less envy than minimal inequality,” with its attendant veneer that the slightest shifts of fate would have made all the difference. (It is worth noting that Schoeck does not spend much time investigating the factor of gender in the phenomenon and perception of envy, and perhaps it does not come as a surprise that the authors who do, are female. Plus, Schoeck’s book was published in the sixties, when “feminist” talking points were just barely beginning to breach the mainstream.)

—

I do identify as a woman; I am also a card-carrying American, for better or for worse. So while writing this, I was reminded of a passage I read many years ago that has stayed with me ever since: an excerpt from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy In America, from the chapter subtitled “Why The Americans Are So Restless In The Midst of Their Prosperity.”

For background: between 1835 and 1840, de Tocqueville published the two volumes of his landmark text, a cumulative 700-page behemoth, in which the French philosopher, aristocrat, and diplomat contemplates the democratic revolution in the United States. Although he does not explicitly name envy as the widespread contagion he describes in this section, his evocative descriptions of “free” yet excessively harried men besieged by anxiety summon the sin and its attendant torments.

De Tocqueville depicts the democratic environment in the young nation as having yielded a proverbial playing field in which, theoretically, “all the privileges of birth and fortune are abolished,” and “a man’s own energies may place him at the top.” Although this may be the initial perception, de Tocqueville remarks that it “is an erroneous notion, which is corrected by daily experience,” since “the same equality that allows every citizen to conceive these lofty hopes renders all the citizens less able to realize them.” In other words, the Americans “opened the door to universal competition” and all of its concomitant miseries. De Tocqueville then pivots to attenuate his own definition of this “equality,” noting that there will never be such a concept “with which [men] can be contented,” as “they will never succeed in reducing all the conditions of society to a perfect level.” Plus, “even if they unhappily attained that absolute and complete equality of position, the inequality of minds would still remain,” as de Tocqueville attributes these to “the hand of God” and thus unable to be configured by man. In this sense, Democracy in America predicts and reinforces Schoeck’s edicts, over a century later, that even if, somehow, the deplored political systems of communism or socialism were ever to be adopted, envy would not be successfully eradicated, so embedded it is in human nature.

—

The quintessentially American rat race de Tocqueville discusses became real to me only after I graduated college, having completed the tacitly agreed-upon course set out by my upper-middle class suburban environs. I became involved in sex work at this point for several reasons that are not remotely unique, but one is most relevant here. For me, pursuing a role in this industry has been rooted in a sustained interest in avoiding formally, thoroughly becoming a member of Society™, as denoted by its claustrophobic, mind-numbing participation in rituals I deemed absurd, or soul-crushing, or outside of my capabilities, or all of the above. I thought that the most effective way to eschew the world was to cache enough cash to minimize requisite forays into our loathsome “capitalist realism” (h/t to the late Mark Fisher). Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism (a work which, ironically, I was introduced to through the now-deserted book at this essay’s preface) discusses the concept of “hoarding” in a kindred manner. Berlant explains that due to capitalism’s guarantee of continuous consumption which, by design, fails to fulfill us, in contrast, “hoarding seems like a solution to something.” As such, the act of hoarding “controls the promise of value against expenditure, as it performs the enjoyment of an infinite present of holding pure potential,” likely yielding a “life lived without risk, in proximity to plenitude without enjoyment.”

Adam Phillips, in On Balance, relates the concept of urgent accretion to the possibility of becoming “greedy out of envy,” recognizing that our objects of desire “don’t actually belong to” us, although we “depend on them being available.” Instead of tolerating this reality, we “would rather destroy [these objects] with greed,” of which hoarding is a conspicuous permutation. Stockpiling “is a way of avoiding making choices,” since if one has everything, there is no need for obstructive decisions, inherently entailing “giving up some pleasures for other pleasures.”

The acquisition and accumulation of money in particular is potently symbolic, as it singularly stands for an unbridled freedom that is diminished proportionally to one’s spending. The Philosophy of Money, Georg Simmel’s classic publication from 1900, includes the author’s pontifications on the democratizing ability of money through its winnowing down people’s value into purely “form and potential.” Notably, Simmel writes further about this phenomenon through the lens of sex work (invariably “prostitution,” back then). Declaring prostitution to be “quite specifically confined to the sexual act” and thus “reduced to its purely generic content,” the encounter “consists of what any member of the species can perform and experience.” Simmel goes on to assert that in the dynamic, “the most contrasting personalities are equal and individual differences are eliminated.” These are, plainly, extremely simplistic and questionable statements with which I largely disagree. Nevertheless, the conclusion he eventually reaches is interesting: that “the economic counterpart of this kind of relationship is money, which also, transcending all individual distinctions, stands for the species-type of economic values, the representation of which is common to all individual values.”

—

While digesting and contemplating the above, I was given pause to reflect on the incredibly obvious maxim that once held me hostage with its perceived iniquity: that whenever one is engaged in an activity, one must not be partaking in endless others. Despite being a rudimentary element of human existence, I was all but entirely immobilized when this dawned upon me, with its tentacles of implications. The awareness of how much there truly is, good and bad alike, was dimmed to nearly snuffed-out during active addiction, as my objectives were so narrow and obsessively pursued to the exclusion of all else. Like a zoom-out in a movie frame—starting with a cell and ending with a galaxy—more and more kept entering my peripheral vision until I was staring directly at a legion of lifestyle possibilities.

Inevitably, the question came: How could I ever choose? This paralysis of indecision lent itself conveniently to my tendency toward envy. I longed to be one of those women who excelled in a particular area, because that expertise was, at some point, preceded by a conclusive decision. Or—even more mentally painful for me—it might have never actually felt like a choice at a crossroads was made, if the designated course presented itself as so compelling and self-evident. What comfort there must be in such conviction!

–

The imperiled field of sex work is a veritable battleground for all genres of political and sociocultural players. As Julia Bryan-Wilson wrote in “Dirty Commerce: Art Work and Sex Work Since the 1970s”: “‘The prostitute’ is stretched thin across the threshold of the literal and the metaphoric, put to work as almost no other figure is.” Marx et al. have asserted that all forms of labor under capitalism are essentially variations of prostitution; Bryan-Wilson notes that “the instability and porousness of the metaphor itself” makes this dangerous, as “it cannot be contained, it cannot be reined in, it cannot help but quickly skip down the chain of associations, back to the body and into the realm of the lived.” As this implies, the literal selling of sex is its own unique exchange, intersecting with fundamental questions about personal agency and women’s sexuality.

In Temporarily Yours: Intimacy, Authenticity and the Commerce of Sex, Elizabeth Bernstein draws on her own field research to explore “bounded authenticity,” the term she gives to the paid but convincingly intimate interactions most desired by 21st-century clients. Class is inextricable from the history of sex work and its current presentations. Increasingly adopted by sexual service providers since the 1980s, Bernstein outlines the “playboy philosophy,” emphasized by an “intensified focus on the creation of ‘atmosphere’ and luxury.” These people, places, and things “have proliferated to cater to clients’ fantasies of consumptive class mobility,” leading to clients viewing “the sexual marketplace as the great social equalizer,” granting them access to “a caliber of goods and services that in earlier eras would have been the exclusive province of a restricted elite.”

Female sex workers are thus principal actors in an episodic psychodrama that aims to realize the manifold, class-conscious fantasies of a male clientele. In the course of this role embodiment, one’s marketing strategies are crucial to the crucible of craving. Envy, at least for me, thrives in this context. In spite of the years I’ve spent puncturing and deflating the presumptive impressions of those inspecting my own online presence, I have found it vexingly difficult to extend this logic to others. Still, a high-end escort who posts photos and videos of herself rolling around in crisp bills, reclining by the pool at an island resort, and wearing exclusively designer lingerie may, in un-curated reality, be in circumstances that are down at the other end of the solvency spectrum. But the production of fantasy is as central to sex work as the sensationalized carnal acts themselves. If someone is good at constructing and maintaining a professional persona, it will feel incontrovertible in the eyes of the beholders, whether they’re attached to potential clients or others. Even though I should perhaps “know better,” when I am at my lowest, I find myself highly susceptible to buying the pie in the sky they’re selling.

(Note: There is certainly a subset of men—usually found on the “sugar daddy” websites—who get off on believing that they are swooping in to rescue a struggling student or a starving artist. But to get too close to the actuality of anything approaching true poverty and destitution is a boner killer, exterminating the illusion and snapping erotic escapism back to the facts of life’s brutal inequities. Also, male envy arguably comes into play full-force with the affairs spawned by platforms like Seeking Arrangement, as these relationships are often intended for flaunting, for showing off that a worldly man is capable of ensnaring a beautiful piece of female arm candy. Though it may be unspoken common sense as to how exactly the dynamic formed and is sustained, there’s still undoubtedly a sense of pride and a desire to inspire envy in their male peers.)

—

How envy affects me at this point is a far cry from the suffocating, stifling emotions from several years ago. That being said, I have not fully escaped its talons, despite—because of?—decisions that have limited my opportunity and my ability to partake in both sex work and artistic production. My 2019 resolution to attend nursing school came after a series of personal, internal revelations (see A Soliloquy On Scrubs). Following through with this plan (as Covid interrupted my completion of the prerequisite courses), struggling to prevail over the subsequent licensing exam, and adjusting to full-time legal employment for the first time in my life devoured vast reserves of energy that impacted every aspect of my existence. Removing myself from the depth of the trenches of sex work and art did, needless to say, shift both perspective and priorities, focusing my attention on pursuits with far different criteria for success. As I was watching my nursing school peers pass the NCLEX right away, while I had to slog away until the third time was the charm, I was exhausted and exasperated, but not consumed by envy. I can now identify that this was because I did not—and still don’t—assign the same value to the manifestation of qualities relevant to these academic and professional victories.

And yet, I would find myself restlessly agitated as I spent nearly the whole year post-graduation studying for and botching the licensing exam. I’d chew my cud: “If only those influential figures in the art world who had expressed such enthusiasm for my work years back could have given me the exposure boost I needed to continue the momentum… If only I had landed a wealthy benefactor falling over himself to finance my artistic endeavors…” I told myself that had these wishes—which, almost always, relied on the actions of others—come true, I could have made a full-fledged career out of my creative exploits and wouldn’t be sitting at the library yet again, witnessing my long-harbored fears of failure reach over-ripe fruition. During study breaks, I bitterly noted the apparent continued triumphs of a handful of women who outlasted all others as my envy’s final bosses.

These reactions have not entirely disintegrated; as recently as a few weeks ago, I was thrust in to an hours-long spiral upon being unexpectedly confronted (thanks Spotify) with the most recent output from my dormant resentment’s ultimate prized recipient. Upon seeing the [impressive] stats re: track plays and general engagement this person has racked up, I settled into my undeniably comfortable dungeon of self-pity and envy. There, I indulged in some of my least favorite—but most sharply acuminated—thought patterns: that should have been me.…why is it them?…are they really that much better than me?…it’s because they are more conventionally attractive, isn’t it?…let me enumerate all the ways my life would be different if the fickle general public (plus my own followers, who apparently only want T&A and don’t care about what I actually put effort into) appreciated my creative labors more…

—

I have had to ask myself, over and over: Why do I feel most harassed by envy in the domains of sex work and creative productivity?

Clearly, the answer is that what is required to flourish in these fields—and, to a somewhat lesser extent, the spoils of such success—is aligned with what I value most. The lowest-hanging fruit here (principally for sex work, but by no means irrelevant in the art world) is being recognized and prized as physically attractive. My formative pubescent years were pillaged and plundered by a lengthy awkward phase that ravaged my fledgling confidence; and though I’ve been blessed with a fast metabolism and an alluring waist-to-hip ratio, the “butterface” brand has plagued me ever since, in 2011, I reverse image-searched my OKCupid profile pictures and found an entire thread on a proto-incel message board analyzing exactly why I’m so hideous. Up until relatively recently, this combination of factors left me desperate for male validation.

More so than a consistent confirmation of sexual desirability, though, it is the inner discipline needed to excel in these two categories of independent contracting that I envy. Growing up, I was allowed to quit all ventures I started that I didn’t immediately excel at (so, everything), partially as my parents’ attempted antidote to their own childhoods, during which they were spoon-fed a firm, specific vision of grit, persistence, and duty. Unsurprisingly, this state of affairs did not set the stage for a prospering of perseverance in my psyche. Without a mindset that propels toward striving and effort, even the most drop-dead gorgeous, brilliant, talented among us is wasted and withers. By repeatedly daring to try—and, by extension, fail—out in the world in various contexts, muscles are exercised and capabilities honed, including the development of a certain competence at navigating a range of social situations. This is next to impossible to achieve solely via one’s imagination (or through primarily virtual affiliations), in a condition of constant isolation bred from fear. The self-promotion integral to climbing the ranks in sex work and the art world alike depends on understanding how to handle super-charged social interactions surreptitiously and casually, assuring prominent players that they are of interest beyond their usefulness to one’s career.

The lines of my envy blur and bleed most strikingly when considering creativity’s role in success in these twinned areas. Particularly when it comes to sex work personas, there is a heap of formulaic tropes that have plowed on and persisted, and that is, of course, because they’re effective. Regardless of the money made or attention gained by the embodiment of such tried-and-true stereotypes, I find my envy only minimally stoked in these circumstances. But when an element of the unexpected is incorporated, hinting at the presence of something beyond adopting what is already known to increase salivation, I perk up and really take notice, often to a tragicomically distractive degree. This internal response suggests that what I truly, deeply envy above the rest—the financial security, the confidence in attractiveness, the social aptitude—is someone who has all of these, plus that unique, ineffable extra expressed through an artistic medium, signifying the possession of an innate gift. It is frustrating to realize and accept that my most virulent strains of envy, once anatomized, boil down to the longing for that which I cannot practically aspire to. Even the highest levels of discipline and charisma fall to the wayside, for me, in the absence of this.

—

Schoeck wrote: “Once the process of envying has begun, the envious man so distorts the reality he experiences, in his imagination if not actually in the act of perception, that he never lacks reason for envy.”

I hope that I can reverse, or at least ameliorate, the damage my envy has done, by “simply” living and doing and, above all, trying.